How to Panic Judiciously: An Interview with Ira Allen

Or, humanizing in the face of "hotter, darker, weirder" days to come.

Now that I’m back from vacation, I am happy to share with you an interview with my friend,

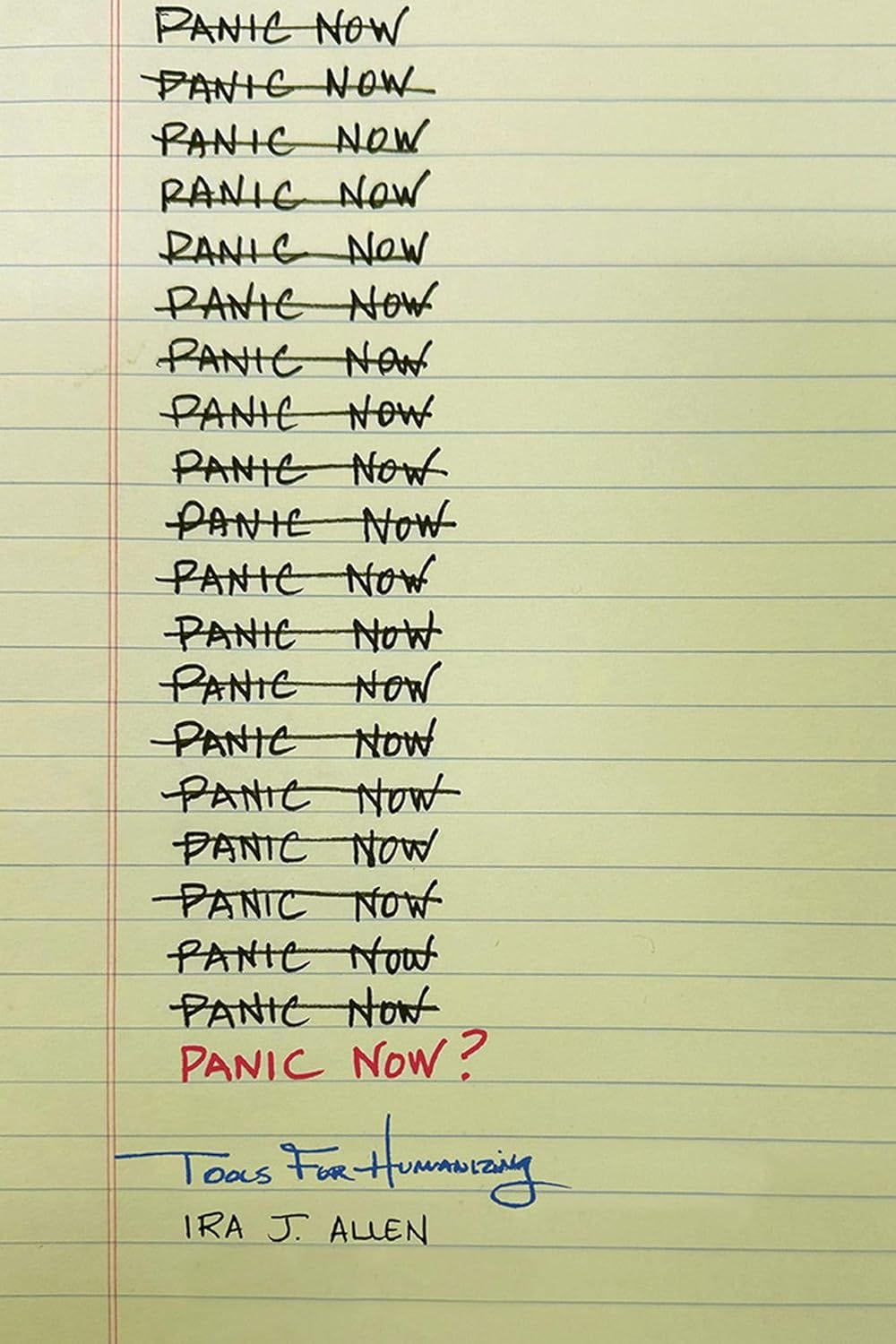

, author of Panic Now? Tools for Humanizing, which will be out in a few short weeks from The University of Tennessee Press. I had the pleasure of reading both an early draft manuscript and page proofs of the book, and let me tell you: don’t miss this one.Cover image of Panic Now? Tools for Humanizing. Image courtesy of The University of Tennesse Press.

In the book, Ira details four overlapping crises that we all feel on a visceral level: climate change, the novel chemical crisis, the sixth mass extinction, and, of particular interest to readers of Prose & Processors, AI. In the first half of the book, he argues that these crises are the “deferred costs” of our current Carbon-Capitalism-Colonialism (CaCaCo) political-economic system, and he further argues that panic is both necessary and wise as a response, so long as one panics judiciously. As he explains in the second half of the book, to panic judiciously is to humanize—that is, to find or create new ways of accompanying one another and helping one another live well, or at least as well as possible, in what he calls “hotter, darker, weirder” conditions.

Ira has much to say on this—more than he includes in the book, and more than we could cover in three hours of conversation. I have excerpted what I take to be some of the most salient points from our interview for readers of this Substack, but I highly encourage you read the whole interview and buy the book. You won’t be sorry!

Interview Highlights

On the place of automation and the dehumanization of labor in CaCaCo:

And so we live in this Carbon-Capitalism-Colonialism world, and this CaCaCo order costs things to sort of achieve, create, you know, forge or whatever, however you want to put it. And bottom line, the costs that made this possible turn out to include any number of deferred costs that were previously understood as externalities—so, things like carbon accumulation in the atmosphere, nitrous oxide accumulation in the atmosphere, or methane accumulation in the atmosphere or things like the unviably dehumanizing and damaging forms of life associated with colonialism for many of the colonial subjects throughout the world.

And this [last] is probably some of what we'll talk about today: The drive towards a fully automated world in which labor is never recouped exactly, but value is only ever accumulated for those who already have capital in ways that are at odds with the humanizing of labor forces.

On the difference between “artificial intelligence” and “automated intellection”:

We don't really know what we mean by intelligence. Nobody. I mean, we've been arguing about what we mean by this lots and lots over a long period of time. Now, that's true for any kind of contested big term. That's true for freedom. It's true for democracy. So that's not necessarily a mark against talking about intelligence. Most of our cultural topoi, we don't really agree about what exactly they mean when you drill down.

But intelligence as a cultural topos sponsors a lot of not-so-great conversations. Such as like, you know, scientific racism, for instance, or the contemporary rebirth of eugenic movements, especially gene editing visions. So intelligence is just a word that we should be a little leery of. That doesn't mean you can do without it. It is a word that helps us map the world in ways that are somewhat useful, but we do want to be a little careful in terms of where we put it in our sort of pantheon of terms.

It's really freighted in these ways that you can't just disavow and have go away because they're live. They're not just historical propositions, but ongoing, living propositions.

In a more like, what-is-AI-level reason? It's actually about parsimony. For me, it's about observability. What I can observe with AI, and what anybody can observe. We actually are not very capable of observing the reinforcement learning processes at a granular level. We can understand them perfectly well at the level of knowing what transformers do in general and knowing how large language models work in general, but at a granular level, we're not really able to tell quite what's happened in virtually any given instance.

Thinking about that as intelligence sets up essentially a theological posit about what's happening inside of the machine. There's something happening that is like what we think it is to be human. The reason intelligence is such a freighted word in the first place, is because it's interwoven with what we think it's like to be a person, a human person, a dog person, an orca person, a swarm of bees person, an octopus person. To be a person is to participate in some way in something like intelligence.

We may well need, in the relatively near future, to actually regard AI as as persons. To me that's not like a hard stop of possibility at all. But in terms of what's directly observable at the moment? That's not observable. It's just sort of a ghost in the machine kind of posit.

What is observable is that what we call AI, what we call artificial intelligence, and this is gonna sound a little tautological, it produces intellection products. You input some form of symbolicity, and the machine spits out some new form of symbolicity that is recognizable in terms of intellection; it is recognizable as the sort of things that intellects produce. Is there an intellect producing it? Who fucking knows? Probably not, at this juncture. Probably, before too long, realistically.

So the value of thinking about what AIs do as intellection product-making lets us say, “what is here?” What are you, what am I, what is your student, what is a tutor in the writing center, what is a junior programmer, a junior developer, what is a senior sysadmin, what is an AI coder themselves interacting with?

Well, they're interacting with intellection products.

. . .

The value of doing that with automated versus artificial is mostly for me to emphasize that what's at stake is not artifice, in fact. You're not making a bespoke artifact that works in the way that you, the maker, know it's going to work. You are making a self-organizing process that you keep tinkering with, hoping it's going to spit out the intellection products that your audiences would be looking for. But ultimately, that process is, to a large extent, self-organizing.

On the panickable problem of AI at scale:

I think those thinking about what AI means for them are not thinking about what it means to have meaning robbed at all levels all of the time from different intellection processes.

. . .

There's lots of bullshit jobs, bullshit work built into the structure of a sort of neoliberal capitalism's reporting imperative that's written into everything that we do. And people understandably say, “Well, I don't feel like I should have to do this bullshit work, like, this is not meaningful to me already. Why shouldn't I automate this? The product has to be created. But actually, it doesn't require me, not in a strong way, in the loop. I [can] just kinda look over it and make sure that it didn't, like, fuck it up.”

And the point is, for any given person asking that, if they are right that the work is bullshit work, which is debatable and variable, but if they're correct in their assessment of that for them personally, that is actually a good. This has taken some cognitive loading that was meaningless off of their plate.

. . .

[But somebody] has to look at all these things that actually are totally meaningless. That person cannot then audit some collection of those annual reviews to see what faculty members thought they were up to. They can audit those collection of reviews to see what a machinic summary of what faculty members were up to included. And that machinic summary does not have a guarantor of meaning in a human person and an intelligence back behind the intellection product.

. . .

So you can see that there's automatically a problem: [the human person doing an audit] can't know whether the text that they're engaging with has been generated by a process that involves a human guarantor behind the text.

Now add in a further dimension. Because of the way that AI statistical inference processes are built to sound more human or feel more human, they produce intellection products that are more human or more human-like by not, in fact, just doing whatever’s statistically most likely, but, rather, doing something that's tinkered with and weighted in different ways.

There is the guarantee on top of this that some amount of what you're seeing will not be true at all.

. . .

You now don't have any real referentiality available to you. You have no way of determining how to make sense of all this, because you have no reasonable expectation that behind each piece of writing there is a human intellect trying to roughly tell the truth.

. . .

It creates a set of conditions that is absolute havoc for meaning-making.

On panicking about AI:

Humans are not able to opt out of symbolicity. And so this is the general problem of generative AI as a new dispositif. We are very likely to enter into a near future wherein vast swaths of the intellection products that each of us encounter are machinically produced to ends that are inimical to our own in ways that we're not entirely able to opt out of processing or negotiating.

On panicking about AI judiciously:

We've got like this discourse in higher ed around AI and cheating. And we have, I would say, like broadly, three camps. Camp one is: The students are using it to cheat, and it robs our entire enterprise of meaning. Camp two is: stop interfering with democratic access to writing. Every new tool is decried by the old guard, and they all turn out to be okay. And, moreover, like, using the new tool is part of the meaning of the college activity. Camp three is, oh, my G-d! I just don't wanna think about this.

. . .

Each of these positions actually has some really important insights for understanding how we navigate AI at scale.

That's, you know, sort of an easy thing to say. Everybody's right! Aren’t I nice? But there is a sense in which it really is the case. If you really wanna think about how things will unfold at scale, you do have to think about a “meaning-robbing” element. You do have to think about a “negotiating capacities” element. And you do have to think about a “how do I opt out?” element. Each of these camps has a core insight. And actually, all three of those core insights are part of what it looks like to judiciously panic.

And the question of how to combine these is the question of judiciousness, of wisdom, of phronesis, practical wisdom, a core product that we offer as rhetoricians.

What does it look like as AI scales in the larger world? What does it look like to take the “this robs things of meaning” people seriously without trying to shut them down? What does it look like to say, “oh, we've got to be able to negotiate this” without tilting over into a grift or into unnecessarily mocking those who are saying, “this is bad. I don't like it?”

What does it look like to navigate a world where it is extremely likely that a huge amount of the intellection products that any given human being encounters will be machine-generated with very little direct reference to the desires of a human artificer?

On adjusting pedagogy in the wake of AI:

I'm doing stuff that I didn't used to do but that I probably needed to do anyways, which is a little more close reading in class, rather than just discussion about texts: actively, literally reading them out loud. And I've always done some of this—so, one of the things I usually do is we'll we'll pick a paragraph. Let's say we're reading Burke's essay on terministic screens. This is a sophomore level class. This is a hard essay for sophomores to jump into, but they do a good job with it. I mean, I think we share this pedagogical attitude. Students can actually really do a lot if you ask them to do it, and you give them the tools for doing it. They don't need textbooks about it. They don't need long introductions to it. You just have to go slowly with it, and they will do it. But the trade-off is, you can't do as much stuff if you do that. So that's, you know . . .

That's the essential curricular trade-off. How much stuff do you want to do, versus how much capacity do you want people to get out of each thing that they're doing? I go pretty hard on the capacity side of that. I'd rather spend, you know, THREE weeks reading one essay by Burke, and another two weeks reading one essay by Kris Ratcliffe.

Everybody has some ways of making meaning that are based on a rich, felt sense of moving through those texts. What I feel like I have to offer as a teacher is about helping people pursue the motion of the thought.

. . .

If you wanna have more capacity to negotiate constraints, which was a big focus of my first book, if you want to have more capacity to be a person who is participating in your own becoming in the world, you gotta go slower.

As the AI dispositif becomes more and more capable of disposing us in ways that reflect our predispositions, it's all the more valuable to be able to go slow, to choose, and like you say, to be able to enjoy that. This has been part of my pedagogy for years, like there is a kind of joy to going slowly with the text and doing something with it that you felt like you couldn't do, and then you can do, and the thing that you do with it is so much cooler than what you thought it was going to be when you glanced at it, ran away from the feeling of difficulty or panic or incapacity, and bullet-pointed it.

I think I think we owe it to students to help them develop that mode of being.

On humanizing with AI:

One one of the things I'd like to see us starting to do is in the same way we see some municipalities pursuing municipal power co-ops or solar, or whatever, I'd really love to see us pursuing municipally collaborative AI systems that that invite multiple stakeholders to participate in parameterizing the language learning models’ processes.

. . .

If you want that, you know, you can do it. You can actually get really, really far. There's a lot of capacity that you can build with relatively small language models. It doesn't have to be giant supercomputer clusters. At this point, it's possible to piggyback off a lot of the work that's already been done, basically to do things that are less resource-intensive. What does it look like to build Community AI that's housed locally? That doesn't rely on Amazon cloud servers? That doesn't rely on a new interface for somebody else's model? What does it look like to do that at a small scale? I think a lot of this kind of work (and this gets at the question about artifacts), whether it's building community meshes with Raspberry Pi to pursue wireless connectivity during a period of highly predictable wireless breakdown, or it's pursuing municipal power co-ops or it's pursuing, you know, community-based AI. I think any kind of project that somebody feels themselves called to do that cuts across existing hard, entrenched [opposed identities], opens pluralistically to a broad vision of humanizing.

And this is maybe a kind of a hopeful note to close on. Like, we're actually in an era of collapse and dispersal and things going exceptionally badly. That's all going to happen. But we're also in the era where new kinds of social experimentation can reasonably hope to pay off in new world-building possibilities for the first time in a very, very long time. And that's super exciting.

The Interview Entire

Note: This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Christopher Basgier: I'm joined today by my friend Ira Allen, Associate Professor of Rhetoric, Writing, and Digital Media Studies in the departments of English and Politics and International Affairs at Northern Arizona University. As a rhetorical and political theorist, Ira has authored, co-authored, edited, or co-edited over 20 chapters, articles, and special issues of journals.

His first book, The Ethical Fantasy of Rhetorical Theory, was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 2018. His second book is our main topic of conversation. Panic Now? Tools for Humanizing is out at the end of July, and it's available for pre order from the University of Tennessee Press.

In Panic Now? Ira details the scope of 4 overlapping crises facing humanity, including the proliferation of generative AI. He argues for judicious panic in the face of those crises, and he gives us tools for accompanying one another more humanely through the worst of what will come. Ira, thank you so much for talking with me today.

Ira Allen: Thank you, Chris. That's a fantastic introduction. And yeah, thanks a lot for having me. I'm delighted to be in conversation with you.

Christopher Basgier: As you know, my readers are mainly interested in AI, but I think it's worthwhile for them to understand what you characterize as this current kind of polycrisis. So, can you summarize that in broad strokes for us?

Ira Allen: Big picture—and I only deal with 4 dimensions of this in the book, but you could proliferate them. It's not just that there only are 4 dimensions, it's just simplest to focus on four—the polycrisis is the general state of affairs, characterized by multiple overlapping, accumulating, stacking, resonating, unfolding crises that together constitute conditions of impossibility for the maintenance of “normal,” as we've understood it for the last 20 or 30 years.

Christopher Basgier: So. And what are those kind of overlapping, stacking components? And why won't they let us stick with the normal?

Ira Allen: Yeah, so in the book I talk about this in terms of CaCaCo, the Carbon-Capitalism-Colonialism assemblage. And basically we especially, we beneficiaries in the global north, but also like a fairly large beneficiary class in the global South—increasingly large in the last 20 or 30 years—we live in a world that is enabled in terms of production and consumption by extraordinary carbon spend. It's organized legally by the structures of colonialism: the many, many legal residues and ongoing sort of maintenance procedures for a colonial world order. And it's organized in terms of productive and governance capacities by the political economies of capitalism.

And so we live in this Carbon-Capitalism-Colonialism world, and this CaCaCo order costs things to sort of achieve, create, you know, forge or whatever, however you want to put it. And bottom line, the costs that made this possible turn out to include any number of deferred costs that were previously understood as externalities—so, things like carbon accumulation in the atmosphere, nitrous oxide accumulation in the atmosphere, or methane accumulation in the atmosphere or things like the unviably dehumanizing and damaging forms of life associated with colonialism for many of the colonial subjects throughout the world.

And this [last] is probably some of what we'll talk about today: The drive towards a fully automated world in which labor is never recouped exactly, but value is only ever accumulated for those who already have capital in ways that are at odds with the humanizing of labor forces.

So, like, as these dimensions of an assemblage that are all interwoven turn out to produce deferred costs that the system as a whole can't pay, the system as a whole will stagger through a period of collapse. And that doesn't mean the old Mad Max. I'm not talking about Mel Gibson riding around in a muscle car shooting bikers. Right? It's not, like, the nihilist vision of collapse.

What “collapse” just means is that one form of global complexity obtains, and that form of global complexity is organized by supply chains, by the capacity to produce agriculture that sustains a population of 8 billion-ish and growing, by this notion of green growth, where, no matter when we do, like, the just energy transition, the pie will always grow by sort of ongoing technological complexity. We see this obviously in the AI revolution, but not just there: also longstanding processes of not just automation, but also like just complexification of technological capacities across all sectors of society.

So as the forms of complexity associated with CaCaCo break down under the weight of deferred costs that cannot be systemically paid, what you'll end up with is a differently ordered world. And that means new organizations of violence. Right now, we live in a world that's organized by massive, ongoing amounts of violence. But they're organized along the old colonial lines, effectively—not perfectly, not without like revolutionary upsurges here and there, but, broadly speaking, for (certainly since the fall of the Soviet Union) a mostly hegemonic sort of global organization that carries forward the old colonialisms. And we see in Russia's invasion of Ukraine, also the old Soviet version of colonialism also gets carried forward. You've lost the socialism. You've lost the communist horizon for Russia. All that's long gone. But the vision of a kind of coloniality, of some kind of metropolis, some kind “most important,” “most human” populations, and then dehumanized hinterlands—that's the world that we to a large extent already live in and is mostly invisible to most of us in the global north, who, you know, don't have to think about the child slave laborers lifting cobalt in DRC, for instance.

So that's “normal.” And that's obviously not great. That's bad. But that's normal. That's the normal we live in. And my point in saying that is, there's massive amounts of sort of what's sometimes called by political theorists “slow violence”: essentially, structuralized forces of violence that play out in highly predictable ways. Exactly who they harm is always sort of contingent. But they play out in highly predictable ways. And we're entering a period of more stochastic reorganization of complexity, and probably a less complex overall world.

Which isn't to say there won't be massive pockets of complexity. You can imagine the future of sort of smart cities and benighted hinterlands. Like that's quite easily seen as feudal agricultural hinterlands sort of forcibly supporting smart cities. This is actually the vision Jodi Dean articulates in her work on neo-feudalism.

Christopher Basgier: So forgive me. But has there been, or can you imagine, a political economic system that doesn't have some kind of massive deferred costs?

Ira Allen: That's a great question. I mean, yes and no. This is one of the ways in which I'm not a very orthodox anarchist. I'm not a good member of the left. One is supposed to believe in the capacity of totally hierarchy-free worlds, if we can only get the conditions right. I don't really think that's feasible. And I write in the last chapter of the book, I talk about the ways in which something like hierarchy is, I think, an ineliminable fact of being a symbolic animal, and once you have hierarchy, you're always gonna have some set of deferred costs. Some set of costs are imposed upon those who are more or less subjugated relative to a hierarchy.

Now what that looks like can vary enormously. When we look at the human historical record, we see so many different kinds of collective self-organization. And they don't all have the same drive for a kind of overreaching complexity. And they don't thus don't all produce anywhere near the same levels of deferred costs.

And this is probably a bigger conversation, a different conversation than we can really get into right now, but I think in general symbolicity as such imposes deferred costs. To be a symbolic animal, to be an animal that lives in symbols, is to be constantly referring to a world that is not the symbols. And the process of reference imposes a cost on audiences, and none of those costs are ever paid in full because the audience always refers to a slightly different world.

Symbolicity is in general the concatenation of small, deferred costs. But to think of that at one level of analysis (as something that's intrinsic to being a symbolic animal) isn't necessarily the same as thinking of it at another level of analysis, which is the analysis of a globalized culture or system. You know, you don't have to end up with that from this.

And I think what's important is to be able to look at the historical record and say, human culture groups have organized in lots and lots of different ways. They all impose some deferred cost. That's part of the deal. But the kinds of deferred costs that they impose are not always such as cannot be paid by the systems that they develop, and the kinds of deferred costs that they impose are, until now, never so global that they're going to be paid by everybody, regardless of whether they've been beneficiaries or not. And that's what's really different. This is a radically different moment in human history. Everyone will be paying the deferred costs. Period. I mean, the very wealthy will find ways out of paying for as long as they can, as they always do, but everybody will be paying some of the deferred costs of the failure of CaCaCo.

Christopher Basgier: That sets up the next question, really well, actually. So, these deferred costs are coming due in the forms of climate change, the novel chemical crisis, artificial intelligence, and the 6th mass extinction.

So in the face of all of that, you argue for judicious panic. Can you tell us, how do you define or characterize judicious panic? And why is that preferable to a kind of stoic calm in the face of these crises?

Ira Allen: Yeah, that's a great question. Amusingly, actually, I just today saw a great mock ad for a new British political party that would be called the Oil and Gas Party and in the satire part of the tagline of the Oil and Gas Party is, keep calm and carry on drilling, and I think, like when we think about calmness, and we think about stoic sort of responses to difficulty, the core of what we think about is how to maintain a kind of stable core relative to the endless flux of the world. I mean, that's basically the point of stoicism as a philosophy, like ancient stoicism. There's a sense in which what we want from keeping calm is basically to produce maximal stability.

Under a lot of conditions that's actually basically reasonable. Under conditions of relatively transitory flux, being able to be an ocean of calm in a sea of madness is actually, like, evolutionarily adaptive for the species as a whole, to have sort of creatures that produce superordinate modes of being relative to the flux of everything changing.

That's true when change is, you know, transitory. In other words, when we're in processes of small scale system change, keeping calm is basically a good idea. In a way, keeping calm is about maintaining stability in the context of flux. I mean, I'm oversimplifying a little bit. But that's part of what we hope for out of a kind of stoic philosophy.

But when we're talking about radical changes in the material organization of life? Part of what's at stake in panicking is saying simply, “The conditions that obtained, the horizons that made my activities make sense, that contained them, are not available for the future. Oh, shit!”

Panicking is one of the central automatic natural responses to recognizing that the horizons that shape your activity system, that shape your conditions of meaning making, are no longer there.

You are still doing what you did yesterday. I'm still doing what I did yesterday, but the horizons that made that make sense are not there, and I know one of the things you think about a lot is the ways in which this is cashing out materially for higher ed. We're looking at some really, really dramatic changes in the higher ed ecosystem.

You and I came up in grad school together at IU at the tail end of a moment. Obviously, people have been talking about the decline of English since the 1970s. We know the story. But we came up in the tail end of a moment of possibility, certainly for rhetoric and composition Ph.D. students moving out into the world and basically all getting jobs.

That moment is a very small kind of horizon. Essentially, like, that's a very particular sort of horizon. And a person who entered graduate school, maybe right around when we were graduating, and I think you might have been [20]13. I was ’14—a person who entered grad school around then, if they had somehow managed not to know anything about the larger ecosystem, they might have experienced a moment of panic a year or two in, as it became clear that things were shifting away from being able to get a job. That small moment of panic in that person's life might reasonably have driven, like, the development of a whole side hustle or a whole other vision of what would be a good way of moving through grad school. Or “do I want to be in grad school?” Essentially, a reassessment of their life. There's lots of things you can be that are not a professor that are meaningful and interesting, right? Or there are lots of things you can do that are not academia-related that are meaningful and interesting.

In terms of the kind of panic that's at stake: It's not necessarily as full-throated as the kind of panic that I'm talking about. But I want to think about that as maybe a little bit of a judicious panic. While it feels quite awful, it is basically a wise apprehension that the horizon they had been working toward, the horizon that they thought was making sense of what they're doing, is gone.

And so what is the meaning of your activity? Maybe it's just like I'm gonna grind maniacally and hope it works. And I'm gonna adjunct until it works. And I'm gonna be super mad or write quit lit when it doesn't work. I mean, people do this. That's one way of maintaining calm in the moment. That's the horizon people end up with when they don't panic, when they're like, no, no, I'm just gonna keep clam and carry on. I'm just gonna grind.

When you panic, it doesn't mean you necessarily stop doing everything. The person might well stay in grad school. They might well still hope to be a professor. But I think failing to panic often produces a “just work harder” mentality that ends up in a lot of sorrow and disappointment, and really bad feelings and panic anyways in the end.

And so this is the second thing: It’s a very long-winded way of saying it. The second thing is when the material horizons are changing so radically that they no longer exist in the way that you thought they did, you will panic. You might not be in it right now. You might not. But you will.

You will, when your house is subject to the storm surge of a hurricane that's not even making landfall near you, that you thought wasn't going to be part of your coastline experience. Or you will, when the property values of everywhere around you absolutely plummet because insurers pull out of the market entirely, and you're no longer able to go somewhere else. You don't have literally the money relative to the system, as it's organized, to just sell the house to buy something else.

We will all panic in our various ways. Maybe it'll be because we're leaving a place, and we're like suddenly leaving at the very last minute. The worst time to panic is at the exact same time as everybody else: too late. That's not good panic.

To come back to the coastal experience: we just had significant flooding in coastal Texas and coastal Louisiana without, in fact, a landfall hurricane, a kind of flooding that 20 years ago really happened very, very infrequently without a much more organized storm system, and that you're going to have more and more and more as the seas rise, and there is more energy in the climate system. That's just how that works.

A person who's leaving their house forever is essentially surrendering the horizon. They're going to do it on purpose sooner, or they're going to do it without another option later. But they're going to do it because that horizon doesn't exist anymore.

That's true for all of us in different ways. But it's true. And this is what's hard, I think, to really cognize, but that, I do think, is widely felt. There's a deep sort of upswell of panic rising throughout most people's experience of the everyday.

You know, people are not idiots, even if they're not thinking about the specific things, even if they're in denial about the things, whether they're in like good blue denial, where it's like “biggest climate bill ever” or oh, you know, “we have an executive order on AI,” or they're in red denial: like, “Oh, this is, you know, natural fluctuations in the Earth system. It's always been like this. It's not even happening.” Anyways, those are just like different kinds of denial.

People who are in denial are actively trying not to have to feel what they obviously are feeling. That's why you produce denial. The whole point of denial is to not be subject to something you are already subject to.

So what I'm saying in terms of panicking judiciously: It's really about like being present with something that's already happening, being present to and with a set of processes of staggered collapse that are already underway, a set of horizon endings that are already in process, and you already feel them. And people know this. They feel it. You see it, especially in young people, because they don't have as much stability in the world. They're just sort of tapping out, and I don't think that that's necessarily the most judicious form of panic itself, either. Panicking doesn't, to my mind, imply “fuck it all.” Panic implies that you still care. That's the whole point of panicking.

I think, like, being present to that feeling and present to that sensibility—that's what opens people up for new forms of invention. And to participate differently in the sorts of invention that will become possible as this world falls apart.

Christopher Basgier: So let's dive into AI a little bit more. Let's do some definitional work first. So you are pretty adamant that you want to refer to AI as automated intellection instead of artificial intelligence. So, can you unpack that distinction a little bit? And I'm curious: what are the stakes in that distinction for you?

Ira Allen: We don't really know what we mean by intelligence. Nobody. I mean, we've been arguing about what we mean by this lots and lots over a long period of time. Now, that's true for any kind of contested big term. That's true for freedom. It's true for democracy. So that's not necessarily a mark against talking about intelligence. Most of our cultural topoi, we don't really agree about what exactly they mean when you drill down.

But intelligence as a cultural topos sponsors a lot of not-so-great conversations. Such as like, you know, scientific racism, for instance, or the contemporary rebirth of eugenic movements, especially gene editing visions. So intelligence is just a word that we should be a little leery of. That doesn't mean you can do without it. It is a word that helps us map the world in ways that are somewhat useful, but we do want to be a little careful in terms of where we put it in our sort of pantheon of terms.

It's really freighted in these ways that you can't just disavow and have go away because they're live. They're not just historical propositions, but ongoing, living propositions.

In a more like, what-is-AI-level reason? It's actually about parsimony. For me, it's about observability. What I can observe with AI, and what anybody can observe. We actually are not very capable of observing the reinforcement learning processes at a granular level. We can understand them perfectly well at the level of knowing what transformers do in general and knowing how large language models work in general, but at a granular level, we're not really able to tell quite what's happened in virtually any given instance.

Thinking about that as intelligence sets up essentially a theological posit about what's happening inside of the machine. There's something happening that is like what we think it is to be human. The reason intelligence is such a freighted word in the first place, is because it's interwoven with what we think it's like to be a person, a human person, a dog person, an orca person, a swarm of bees person, an octopus person. To be a person is to participate in some way in something like intelligence.

We may well need, in the relatively near future, to actually regard AI as as persons. To me that's not like a hard stop of possibility at all. But in terms of what's directly observable at the moment? That's not observable. It's just sort of a ghost in the machine kind of posit.

What is observable is that what we call AI, what we call artificial intelligence, and this is gonna sound a little tautological, it produces intellection products. You input some form of symbolicity, and the machine spits out some new form of symbolicity that is recognizable in terms of intellection; it is recognizable as the sort of things that intellects produce. Is there an intellect producing it? Who fucking knows? Probably not, at this juncture. Probably, before too long, realistically.

So the value of thinking about what AIs do as intellection product-making lets us say, “what is here?” What are you, what am I, what is your student, what is a tutor in the writing center, what is a junior programmer, a junior developer, what is a senior sysadmin, what is an AI coder themselves interacting with?

Well, they're interacting with intellection products.

They're producing parameters. They're putting those parameters together. They're interfering and tweaking the reinforcement learning process to sort of weight this a little bit more, that a little bit less, to essentially try to make statistical inference processes feel more intuitive, feel more human, feel more like human intellection.

Are they in the process producing intelligence? I don't know. Nobody knows that. It's just sort of a theological and ideological [posit]. I don't mean something negative. There's nothing wrong with theology. Theological posits are posits about how the world is that impute something to the world that cannot be known definitively. Will there be a moment in time, in the future, where we can know whether or not intelligence in the ways that we understand it broadly is occurring in AI? Maybe. Yeah. I mean, probably there'll be a moment where AI personhood is sort of undeniable in ways that make us feel like, well, we have to ascribe intelligence to this. But until that moment, it's positing something that we really don't have any way of verifying. It's a very sort of unscientific understanding of what's there is that it's intelligence, whereas [the outputting of intellection products is] what we can actually observe, what's intersubjectively verifiable.

Christopher Basgier: This draws our attention to symbols, and the things that we actually spend our time interacting with, interpreting, making sense of as humans who are symbol-using creatures.

Ira Allen: Exactly, and also, can't not. We're not able to not do so. I mean, whenever it was, a year or two ago, I think it was a couple of years ago, an early iteration of open AI's transformer that it was producing the Zizek/Herzog conversation. Which is fascinating.

You know there's not an intelligence there. You know that there's not a so-and-so producing this, and yet, if you listen to it long enough, you will find it virtually impossible to avoid imputing meaning to it because it's producing forms of symbols that accord with the forms of symbols you and I have been trained to regard as meaningful.

We're going to regard these as intellection products. And we're we're gonna judge them as better or worse, problematic or good. We're gonna regard them in whatever ways we regard them. And that's an ongoing, negotiated conversation, whether there's intelligence or not behind it. That's just something that's useful to remain agnostic about.

And that gets to the automated versus artificial. And this part I'm like less, I don't know, is less important than the intellection versus intelligence thing in my mind. But I think it's, like, it's sort of a tweak that's worth having in mind, just because it's useful to take this conglomerate “artificial intelligence” that comes at us in ways that it's very hard to not get subsumed by the cultural baggage and ideological freighting that comes behind the very notion of artificial intelligence. And so there's a distancing effect, a little torsion in our own understanding or processing we're able to accomplish, kind of like repeating a word, by taking the acronym and recoding it backwards in a different direction.

And so the value of doing that with automated versus artificial is mostly for me to emphasize that what's at stake is not artifice, in fact. You're not making a bespoke artifact that works in the way that you, the maker, know it's going to work. You are making a self-organizing process that you keep tinkering with, hoping it's going to spit out the intellection products that your audiences would be looking for. But ultimately, that process is, to a large extent, self-organizing. That's the whole point of it. That's that's how the reinforcement learning works. And you, the maker of it, are able to tinker with how the automation works. But it is too, in a certain sense, self-automating. Well, I mean, not actually. There's any number of humans in the process. And there's any number, you know as well as I do—you've written about this a little bit in your blog the ways in which there is, you know, exploited labor in the Global South in the loop, helping all this sort of subterraneanly go much like the rest of the shadow work that makes our generally algorithmized world go. But the point is, the going itself is not in a proper sense artifice.

And I wanna be really clear. I am not on the deflationist train here. AI is incredibly impressive, and some of our colleagues who try to avoid their experience of panic by deflating what's happening are totally wrong. They are. I understand, I have sympathy. I think our friends who are hard deflationists are doing something emotionally understandable, but really unwise.

You know, this is a good place to think about judicious panicking. You want to take seriously the way the horizon for symbol production changes when it's possible to automate symbol production. It is now possible, for the first time in human history, to spit out intellection products that are generically and granularly similar to the intellection products that living, breathing humans spit out at a scale and a pace that is absolutely superhuman.

Each platform is associated with a capitalized entity in the world. These are not just, like, scientific things that are happening in a void. Right? These are capitalized entities that have an imperative to deliver value for shareholders at the end of the day. That shapes the way that they unfold, the kinds of intellection products that will be made. But if you say, “what does this platform do relative to a human?” And this is how people are looking at this a little bit mistakenly, for right now people are like, “well, what does, you know, one instance of ChatGPT do relative to one worker in one company?” It's like, well, that's not quite the right way of thinking about this, because one person outputs intellection products. That's what persons do. We put them out and we process them, put them out, we take them in, we put them out, we take them in, we put them out, we take them in.

And one platform outputs intellection products. Puts them out. It takes them in, puts them out, takes it in, which is in some ways actually very different from, say, the Gutenberg press, or mechanical reproduction. When we look at what's happening with the automation of intellection products, we have any given platform able to output vastly, I mean unthinkably, more intellection products in the same period of time than any given human. And so the comparison point isn't your instance of ChatGPT to you working as a mid-salary-range, mid-career developer, and saying, “Well, it can't really do a lot of the things that I can do. Blah blah blah!” Which is true.

The point is to say, in a sort of a John Henry way: when you look at John Henry versus the automatic driver of railroad stakes is that it’s John Henry versus all the drivers of railroad stakes. It's [not just] John Henry versus that driver. It's every person who does this job versus every driver that does this job, because every driver that does this job has to be produced as a unique material entity in space and time and moved around from place to place.

You need a factory that creates these railroad spike drivers, the automatic spike drivers. And then you need those spike drivers actually physically moved around to drive the railroad spikes. But the essence of platform capitalism is that actually, the entity exists in, you know, one distributed space, one set of data centers. So that's what actually has to be compared to any given person because you're not, in fact, moving around the spike driver to compete with every single John Henry.

Christopher Basgier: The spike driver is everywhere, at once, basically.

Ira Allen: Which is so different! And I think it's a kind of scale that people are not good at thinking at, because it's a kind of scale that's actually novel in human experience.

Christopher Basgier: But that scalability is a big reason that you're arguing that this is panickable, right? Because it is already getting to the point—and it's just going to continue to get even more so—to the point that AI generated intellection products are a larger and larger and larger percentage of the cultural symbolic products that we have around us and can't help but read and interact with, and that that has the potential, especially when you think about bad political actors being in the mix, to really shift our culture in particularly problematic ways. And so you, you introduce this notion of the dispositif. Right? So you say, “generative AI is on the verge of becoming a new dispositif, a new mode of disposition for human experiences of culture, and that's worth panicking about.”

So can you tell us a little bit more about how you foresee AI disposing us differently in the nearish future? And again, why, that's worth panicking about.

Ira Allen: Yeah, great. Look. So now you just put the core point super well. I'll just start by reflecting that back again and then kind of pick up on the question of the dispositif, which I draw from my friend the political theorist, Davide Panagia.

So your point about what scale means. That's hard. And again, I wanna highlight: It's really hard for people to think at scale. We're not good at it. There's all kinds of arguments you've probably read or encountered in the book The Politics of Large Numbers. There's a lot of arguments about like, essentially, we're evolutionarily not adapted to a certain kind of intellection at scale. I don't know about that. Maybe that's true. Maybe it's not, but it's definitely the case that we're not very good at it, most of us most of the time.

What this means is that we miss how big of a deal things that happen at scale are. And so right now, I've seen innumerable people making jokes that are like, Oh, man, “I'm gonna automate my 7-year review. This is great. I will never again write an annual review for myself. I'm gonna have, I'm gonna have AI write it.” And besides betraying profound—I think broadly correct, but whatever: profound—cynicism about the nature of reporting in academia in particular, I think those thinking about what AI means for them are not thinking about what it means to have meaning robbed at all levels all of the time from different intellection processes.

If I'm using Perplexity to write my annual review, that does make my life easier. It does take something that is largely bullshit work, and I mean in a David Graeber sense. I'm not just being pejorative. So Graeber talks about bullshit work as tasks that have to be completed because they need to be marked as having been completed. But they have no natural audience. And I think a lot of our reporting in academia, and not just academia but all over the place, has something of this character. It involves a lot of tasks that have to be completed because the fact of them all having been completed does add up to something meaningful. But there is no natural audience for any of the individual intellection products produced along the way. At most, every year, a dean will glance through, at most, some set of people's annual reviews and audit them. Most of them will be read by essentially nobody, maybe their colleagues in the faculty assessment committee or whatever.

So anyways, the point is to say, there's lots of bullshit jobs, bullshit work built into the structure of a sort of neoliberal capitalism's reporting imperative that's written into everything that we do. And people understandably say, “Well, I don't feel like I should have to do this bullshit work, like, this is not meaningful to me already. Why shouldn't I automate this? The product has to be created. But actually, it doesn't require me, not in a strong way, in the loop. I [can] just kinda look over it and make sure that it didn't, like, fuck it up.”

And the point is, for any given person asking that, if they are right that the work is bullshit work, which is debatable and variable, but if they're correct in their assessment of that for them personally, that is actually a good. This has taken some cognitive loading that was meaningless off of their plate. This is the good kind of cognitive offloading, not the not the kind that a lot of our colleagues who are overly celebratory get really excited about, you know, where it's, we're really excited to make reading less [onerous], to offload, to do some cognitive offloading for reading by summarizing PDFs. It's like, well, actually, isn't the whole point of education cognitive loading?

But anyways: [there are] discourses, communication under capitalism as it's currently organized, that are basically meaningless, and that none of them individually is all that much harmed by being done by a machine. The problem is at scale. This has the secondary effect of robbing even only tenuously meaningful processes of meaning.

[Take the moment that a] person has to look at all these things that actually are totally meaningless. That person cannot then audit some collection of those annual reviews to see what faculty members thought they were up to. They can audit those collection of reviews to see what a machinic summary of what faculty members were up to included. And that machinic summary does not have a guarantor of meaning in a human person and an intelligence back behind the intellection product.

You can see if you're at all serious about the infrastructure of the academy that somewhere along the way, that a person does reasonably need to be able to just sort of check and make sure that there are meaningful things happening in the units that they are charged with organizing resources for, to put it in terms that every academic can understand. You don't want the resources going to your jerk colleague who's not doing anything interesting, but pretends that they are. You want them going to you!

(I'm lucky to have good colleagues. Blah blah blah! But you know what I mean.)

So you can see that there's automatically a problem: [the human person doing an audit] can't know whether the text that they're engaging with has been generated by a process that involves a human guarantor behind the text.

Now add in a further dimension. Because of the way that AI statistical inference processes are built to sound more human or feel more human, they produce intellection products that are more human or more human-like by not, in fact, just doing whatever’s statistically most likely, but, rather, doing something that's tinkered with and weighted in different ways.

There is the guarantee on top of this that some amount of what you're seeing will not be true at all. And then you're in this problem, you, this dean, a sort of unsympathetic role for many people who might be in your audience. But I hope they'll stay with us for a second because this becomes everybody's problem here in just a sec.

You, a dean, are auditing your faculty's annual reviews, and you're trying to make sure that you know people are more or less doing interesting, useful things, so that you can figure out how best to allocate the resources you just got from a big donor for a new center. Right? Let's say it's not even zero-sum bad stuff. It's good stuff. If you can't reasonably expect that most of what you're reading is produced with a truthful intent by people who are more or less trying to say things that are reality-based . . .

Now, you do have that problem with human-produced text.

But you have to make sense of [the AI’s production of “bullshit”]. You need to be able to like, look through some portion of it and do stuff with that. You now don't have any real referentiality available to you. You have no way of determining how to make sense of all this, because you have no reasonable expectation that behind each piece of writing there is a human intellect trying to roughly tell the truth.

And I mean tell the truth in a very broad way. Poets tell the truth. Fiction writers tell the truth. There's lots of ways of telling the truth, and you know it may be useful not to think of this as capital-T “Truth,” but more like Bernard Williams, in the book Truth and Truthfulness, as “truthfulness” being a characteristic that makes human symbolic activity work, regardless of whether there ever is a capita-l T truth, regardless of what the conditions for producing truth are or aren't. Trying to say things that refer to the world in ways that would point other humans to the same point of reference is super important to symbols working at all, right?

Now t,ake now take our one little local problem for this one dean, at this one university, and say, this now is the condition for everybody, for the majority of symbols that they encounter in the world.

Suddenly the conditions that make it possible for anybody to sort among the symbols presented for their assent (in good Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca fashion right? The arguments presented for their assent include everything from, you know, images and videos to text, and graphs, etc.)—everybody has to contend with an overwhelming amount of what is now bullshit.

Now, you don't have the option as a symbol-using animal to not try to process it. That's not available. You can work super hard, and you can turn some versions of it more meaningless for yourself. You can repeat the word until it becomes just a collection of marks on the page, and is no longer a word for you, and you can do the same thing with the letter by looking at it long enough. But you can't do that with symbolicity-in-general. You can't do that with the overall wash of discourse; that's not available to you. Moreover, if it were, you would stop being able to yourself functionally produce discourse. It would not be a good outcome.

This creates a set of conditions that is absolute havoc for meaning-making.

Christopher Basgier: Yeah. And it gets worse when you start thinking about it in terms of systems and infrastructures. Right? Cause going back to your dean example, it becomes not only the dean's problem, but if the dean can't authenticate what's happening in some way, then neither can the provost or the Board of Trustees. Neither can the accrediting bodies, neither can the legislature, right? And then it becomes really a crisis in the meaning, in this case, of higher education. But you could apply that to any other kind of industry or sector. And when you start realizing that that bullshit and that scale can become pervasive, then that's where I think the moment of panic really starts to set in, right?

Ira Allen: Exactly! Exactly! Here each of us is John Henry, but each platform is its own universal spike driver. And the universal spike driver is working ubiquitously.

We've got like this discourse in higher ed around AI and cheating. And we have, I would say, like broadly, three camps. Camp one is: The students are using it to cheat, and it robs our entire enterprise of meaning. Camp two is: stop interfering with democratic access to writing. Every new tool is decried by the old guard, and they all turn out to be okay. And, moreover, like, using the new tool is part of the meaning of the college activity. Camp three is, oh, my G-d! I just don't wanna think about this.

Christopher Basgier: Yeah, I'd say that's about right.

Ira Allen: Roughly speaking, you know. I mean, like, I guess there's a camp four, which is grifters, like, ed tech grifters. Not that everybody in ed tech is a grifter. But there's a solid chunk of ed tech grifters, which is basically, “Oh, here's the hot new thing!” They would have been all about MOOCs a few years back. I don't think those people are serious, but they produce a lot of noise, and generative AI allows them to produce even more noise. They are literally a perfect example of, you know, how generative AI can pollute discourse.

So, that's a good example of the bullshit problem that we all face, because you have in these first two camps people who are really seriously and sincerely trying to navigate a real dilemma [and the at-scale production of ed tech grift interferes with their having a real conversation]. I'm quite sympathetic to the experience of the first camp; the second camp tends to quite unfairly describe them as just like reactionary, anti-student. I think that's totally unfair.

So you have the really sincere, really thoughtful second group: What do we do with this? Let's call it the AI literacy bucket. And I put you in that. This is people who are who are essentially saying some version of: “This is part of what we're going to have going on. It behooves us all, especially if we're associated with students learning, to help young people navigate a changing, discursive atmosphere. That's literally our job.”

And then there's “I hate this. I don't wanna think about it,” a bucket which is surprisingly large. It's a lot like, you know, the climate crisis. There's a very strong Don't Look Up vibe. The grifters are on the side of the comet, and the AI literacy folks are like, “Alright. Well, how do we navigate this? How do we? This is a huge thing. But you know, the planet survived the comet before, how do we make sense of this? How do we do things with this?” And there's a huge range, obviously from, like, people who are very celebratory to people who are more—I would put you on the more, as you yourself put yourself, on the critical AI literacy side, which is about, you know: How do you navigate this? So you can do things in the world functionally, because it's part of the deal, without being an uncritical celebrant.

Christopher Basgier: Hopefully, without making things worse.

Ira Allen: I sort of think of you and Anna Mills here. Anna's more celebratory, but she's also still very thoughtful about it. There's this thoughtful side of this, And then there's a little bit of an unkind side of this that's essentially pointing back towards our colleagues, who are unhappy about receiving machine-generated text from students. And they're pointing back to our colleagues who are unhappy about this and saying, “Well, it's because you're a bad teacher, basically, or because you don't love your students enough” or whatever. No: when you're saying that you're not understanding how capable AI is actually.

So anyway, we have many colleagues who are then at various stages of bargaining, anger, grief, you know. They go, “This is awful. I know I need to do something with this. I hate what's happening. I feel like this robs the enterprise of meaning.” And I think, apart from the grifters, each of these positions actually has some really important insights for understanding how we navigate AI at scale.

That's, you know, sort of an easy thing to say. Everybody's right! Aren’t I nice? But there is a sense in which it really is the case. If you really wanna think about how things will unfold at scale, you do have to think about a “meaning-robbing” element. You do have to think about a “negotiating capacities” element. And you do have to think about a “how do I opt out?” element. Each of these camps has a core insight. And actually, all three of those core insights are part of what it looks like to judiciously panic.

And the question of how to combine these is the question of judiciousness, of wisdom, of phronesis, practical wisdom, a core product that we offer as rhetoricians.

What does it look like as AI scales in the larger world? What does it look like to take the “this robs things of meaning” people seriously without trying to shut them down? What does it look like to say, “oh, we've got to be able to negotiate this” without tilting over into a grift or into unnecessarily mocking those who are saying, “this is bad. I don't like it?”

What does it look like to navigate a world where it is extremely likely that a huge amount of the intellection products that any given human being encounters will be machine-generated with very little direct reference to the desires of a human artificer?

Every single platform is, roughly speaking, aligned better or worse. But there are great efforts to make each aligned better with the interests, as they are understood, of a very small collection of humans: the majority shareholder class who own that platform. Period. And those interests are in many ways, relative to the rest of the polycrisis, inimical to the interests of all the rest of us. And that plays out sometimes in really weird ways.

So you probably saw the other day Reuters reported on the Pentagon's antivax campaign in the Philippines. Even I was surprised by that one. I was like, “Oh, wait, really? Like, wow!” This is, I think, a really nice example of what it looks like when a colonially organized power, aligned with a set of capital interests, powered by carbon, sets out to organize public perceptions in ways that are wholly indifferent not just to the well-being of that population but also to literally everybody's well-being. People not getting vaccinated is how viruses mutate. That's how it works. It's well known.

So the immediate strategic interests of power, of some collection of the majority shareholder class, are aligned with people in the Philippines not turning to China for vaccines, but instead waiting longer for vaccines that would be associated with the United States—a historical colonial power in the Philippines, arrayed against China in a sort of a great powers/geopolitical strategy domain. From the perspective of geopolitics, this is a totally rational move. But from the perspective of the highly anticipable consequences, both for the individual people who then don't get vaccines and who needlessly suffer and die in the Philippines, who are totally dehumanized as colonial subjects, and from the general perspective of, like, “What does that mean back in the metropolis for ongoing viral mutation and transmission?”

Those who have the capacity to shape opinions do so in ways that reflect a very narrow set of interests that are not aligned with something like the general wellbeing. And that narrow set of interest that's not aligned to something like the general wellbeing is promoted through discourse that, instead of trying to perform versions of truthfulness, instead of trying to refer to the world in ways that allow for recipients of the discourse to navigate what's said, and then arrive collectively or collaboratively at something like a congress of equals, instead seek to shape, in a top-down way, the minds or the intellects, the intelligences of the human receivers of the intellection products.

There's versions of that that occur all throughout human history. There's nothing novel about that. What's novel is scale. What's novel is the Pentagon can deploy chatbots to do this in the Philippines without actually having somebody needing to sock-puppet those, as we used to say in Internet parlance, where one person would control multiple, different social media accounts. They can instead simply run a script that has each of these accounts automatedly producing bullshit that disposes the receivers of that bullshit.

Because humans are not able to opt out of symbolicity. And so this is the general problem of generative AI as a new dispositif. We are very likely to enter into a near future wherein vast swaths of the intellection products that each of us encounter are machinically produced to ends that are inimical to our own in ways that we're not entirely able to opt out of processing or negotiating.

What it's like to be somebody is to be a processor of symbols. That's what we do. We, like every living creature, metabolize inputs and produce outputs. Throughput is the truth of life. One of the forms of throughput that is particular to humans in its complexity and intensity, although surely not particular to humans in its existence, is symbolic throughput. We metabolize symbols. And we discard, and we also turn those into the organization of life within us. Crows do it, too. Dogs do it, too. Lots of other species do it. We do it at a level of intensity that seems probably higher than most.

And when you add in ubiquitous surveillance? When you add in the fact that data harvesting is the central feature of web 3.0, essentially we live in a world that is fundamentally about taking in as many, many different pieces of our data as possible, even in places that you would think it wouldn't be so. [Even] Mozilla Foundation, which is a notoriously privacy-oriented foundation that owns Firefox, the privacy-oriented web browser, recently purchased an ad server, which is like Google’s ad server; it's a platform for algorithmically distributing ads.

This makes us into informational persons who are sort of coded as this other separate being in the world. We’re in a world where each of us is subjected at a very granular level to constant surveillance.

And when you think about what ubiquitous surveillance allows at the level of disposition. It allows any given [stream of intellection production to be] auto-adjusted in ways that promise to produce at scale and with granularity, at the same time, bullshit that reflects the interests of a very small portion of humanity, and not everybody else. That’s what I think the generative AI dispositif threatens to become. I think it can be navigated or negotiated in ways, but I don't think it is very likely to be avoided.

Christopher Basgier: I'm also interested in hearing you reflect on your pedagogy and how AI and its relationship to writing and rhetoric is affecting your pedagogy, or how you anticipate it affecting your pedagogy, moving forward as well.

Ira Allen: Yeah, so it might sound counterintuitive given everything I've just said, but this is coming out of panic. What I'm about to say is the product of panic. In other words, I've taken seriously at the level of affect a certain kind of loss of horizons, and I've been trying to make sense of that in a variety of ways, including pedagogically.

I actually think I'm bullish on meaning. I'm bullish on interpersonal meaning specifically.

Christopher Basgier: Totally with you on that. Actually, I love that.

Ira Allen: I think that one of the affective correlates of the changing discursive atmosphere towards ever greater bullshit—I think in that context people will desire more meaning. And this is not just AI. It's also, as the general loss of horizons gets more and more intense, when you lose the horizons that secure your experience of meaning, you start looking around. “Well, what can secure my experience of meaning? What is a life for? What is my life for? What do we do now? How does it work? Do I just die? Am I for anything?” And I think these are questions increasingly already that young people are asking. They're asking a lot about the climate crisis more than anything else, I would say correctly. They're starting to ask about AI.

I would say, as recently as last spring, those of us who are looking at this from a more infrastructural perspective (and you know, I know you're one of one of them), we could all sort of see, “Oh, this is going to actually create crises of meaning. This is going to drive things.”

But as recently as last spring, I would say that hadn't filtered through for a lot of young people very much at all. And it's really my impression that it’s just sort of starting to filter through this year. And it's even still not quite there.

If you remember, there was, there was the general assumption that, whatever a digital native is, back in the aughts and early teens “digital natives” would be automatically, like good at tech or whatever, and then it turned out, like, Oh, no, that's not actually true, because if you are native to water you don't really notice it.

And I think we will see for a lot of our students, and we're already starting to see, lots and lots of largely unsystematic, half-conscious engagements with, negotiations or rejections of grifts in generative AI—more or less reflecting the divide within the professoriate and commentariat. I think we'll see lots of students who just don't want to think about this at all. They want to just try to live their lives, man, like, they're just trying to live their lives.

And we'll see lots of students who are doing the student version of the ed tech grifters: “How can I get through my credential without doing anything more than I absolutely have to?”

And then we're seeing lots of students who are like, “How can I, you know, engage with these things in ways that're meaningful and useful for me?” And then we'll see students who are like, “Man, this is bad. I hate that. I hate that my classmates are doing this. This is not good, and I think it's not okay.”

And once more, except for the grifters, all of them have a point.

And so for me, pedagogically, the way that I'm thinking about this is not so much in terms of—and this is really characteristic of my pedagogy in general. I should probably just say, subnote: I am very hard left. I'm hard enough left that you get your guns back. I'm all the way left. I've never once had a student complain about my politics, and the reason is: I don't care what their politics are. My job is not to help them get my politics. I'm not interested in that. If I, like, meet them on the street at a protest, I'm interested then because that's what I'm doing at a protest. But my goal, my aim in the classroom is to help them think. And, like all true ideologues, I more or less think that if they really think they will helplessly end up where I've been!

I think that I need to try to help them engage systematically and thoughtfully and consciously with the constraints of their lives. So for me, AI is just one more dimension of that.

I teach an undergrad course on digital argument, and we do all kinds of stuff. You know, we start out reading some Burke and Ratcliffe, and then we've had semesters where we spent three weeks trying to define influencers.

I've added a section on AI to that syllabus for this year. I'm revamping that course in terms of generative AI writing and, actually, reading especially.

I'm doing stuff that I didn't used to do but that I probably needed to do anyways, which is a little more close reading in class, rather than just discussion about texts: actively, literally reading them out loud. And I've always done some of this—so, one of the things I usually do is we'll we'll pick a paragraph. Let's say we're reading Burke's essay on terministic screens. This is a sophomore level class. This is a hard essay for sophomores to jump into, but they do a good job with it. I mean, I think we share this pedagogical attitude. Students can actually really do a lot if you ask them to do it, and you give them the tools for doing it. They don't need textbooks about it. They don't need long introductions to it. You just have to go slowly with it, and they will do it. But the trade-off is, you can't do as much stuff if you do that. So that's, you know . . .

That's the essential curricular trade-off. How much stuff do you want to do, versus how much capacity do you want people to get out of each thing that they're doing? I go pretty hard on the capacity side of that. I'd rather spend, you know, THREE weeks reading one essay by Burke, and another two weeks reading one essay by Kris Ratcliffe.

Everybody has some ways of making meaning that are based on a rich, felt sense of moving through those texts. What I feel like I have to offer as a teacher is about helping people pursue the motion of the thought. That's why I started by saying the thing about my politics: I don't need them to end up anywhere. I don't really care where they end up. I don't even care if they end up with a good reading of Burke, or a smart uptake of generative AI. That's not what they're going to get out of my class. They'll get that in somebody else's class. What they're going to get in my class is a way of moving through the thought that is, for lack of a better word, the way of a theorist.

One of the core premises of the platform capitalism hype around AI is, “We can make this, you know, less onerous.” I want to say, “Well, no, let me help you do the onerous thing more fully. Let us together become more onerous. If you want to make other things less onerous, cool, by all means, but develop the capacities for doing the onerous thing and enjoying it and finding meaning.”

Then the other element is, you know, a lot of the critical AI literacy stuff everybody's doing: looking at how different kinds of intellection production register different paradigms for how the world works, or different pedagogical visions as you frame it.

Christopher Basgier: What I like about the attention to reading is that it doubles down on meaning. It gives them really that time to figure out. Well, here's how you make meaning: by spending time with ideas over an extended period of time, and not through quick consumption. I mean, there's a time and place for quick consumption of ideas. We've got to do that, especially in this world, right? But if you're hungry for meaning, then slow down.

Ira Allen: Yeah, yeah, that's a great way to put it. If you're hungry for meaning, slow down. Yeah, I couldn't agree more. Yeah.

Christopher Basgier: Otherwise you become a fascist, pretty much.

Ira Allen: Yeah, I mean, you're like, “Boom, okay, cool. I will do whatever I've been told, disposed to do.” That's the thing: if you wanna have more capacity to negotiate constraints, which was a big focus of my first book, if you want to have more capacity to be a person who is participating in your own becoming in the world, you gotta go slower.

As the AI dispositif becomes more and more capable of disposing us in ways that reflect our predispositions, it's all the more valuable to be able to go slow, to choose, and like you say, to be able to enjoy that. This has been part of my pedagogy for years, like there is a kind of joy to going slowly with the text and doing something with it that you felt like you couldn't do, and then you can do, and the thing that you do with it is so much cooler than what you thought it was going to be when you glanced at it, ran away from the feeling of difficulty or panic or incapacity, and bullet-pointed it.

I think I think we owe it to students to help them develop that mode of being. And in this way I'm really, on some level, I have to admit, [a little abashedly] relative to the politics of our world right now, I am really an Aristotelian.

When Aristotle says that the value of studying rhetoric is that you “become enthymematic.” The whole point of the rhetoric is not that it lets you do X, Y, or Z. It's that it helps you become a kind of person, a kind of person who's sensitized to enthymemes, to the unspoken pieces and syllogisms, to the ways in which the world's discursive flows shape us all. You become attuned to that, and you're able to participate in that more richly.

Part of what's at stake with that, in a world where I think we've only just barely begun to see the impacts of AI reading, [is that the changing world is] actually gonna be so much more destructive of our capacities.

When you encounter a foreign text, I mean foreign to you, you encounter the other, and the other makes a demand. And you say I don't know what to do with this demand, and that's what it's like to read right? I mean, like, that's what reading is. And you know, I'm a pretty smart guy, but I have this encounter with new-to-me texts all the time. The demand that reading makes is something that feels kind of shitty—it sucks to not feel smart. It sucks to not feel like, oh, I know what's happening. That's not enjoyable. And at the same time it's really easy to derogate the demand because precisely every single demand made by every single other—this is to your point about fascism—every single demand made by every single other, until I've engaged the demand, the demand’s contents are an empty blank nullity. They're just the demand of otherness. So there's always an efficiency in refusing the demand of otherness, and there's always an efficiency in refusing the demand of the text.

When you have a world that says, “Hey, look! I got a quick way for you to refuse the demands of all texts all the time, and it's going to help you do the things that you need to do to get ahead, make a place for yourself in the world?” I think that's gonna be a very attractive value proposition for an enormous number of people, understandably. Wrongly. Totally wrongly, in ways that are really dehumanizing and rob people of their own developing capacities, but totally understandably.

And this is why I'm centering, maybe more than some of our colleagues who think of it more at the level of writing and bringing to bear judgmental capacities for comparing different kinds of AI output and all the rest of that, I'm centering a value that I take to be core to our entire enterprise. That is about meaning. And I'm letting everything else flow out from that. The core thing is, how can I help you become enthymematic? How can I help you pursue this style of thoughts, movement?