Last week, I had the privilege of traveling to Irvine, California, to attend AlphaPersuade, a summit devoted to considering the role rhetoric might play in building a future where ethical AI is a reality. Two definitions are in order. First, the term AlphaPersuade comes from “The AI Dilemma,” in which Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin of the Center for Humane Technology warn about the many potential dangers posed by the rapid advancement of AI. At about the 43-minute mark, they introduce the term AlphaPersuade to describe an LLM that is trained to be better than any human at persuasion, much as other algorithms are now far superior to humans at, say, chess or go. With models like these, we’re entering a new era of persuasion, one in which computer algorithms move our attention and intention, potentially without our ever knowing. (Incidentally, social media algorithms already do a lot of this persuasive work on us, just without LLMs as their basis.)

All this talk of movement, attention, intention, and persuasion directs us to rhetoric, the second term that needs to be defined. Those of us who study rhetoric are used to distinguishing between “mere rhetoric,” such as political manipulation, and rhetorical traditions with many thousands of years of development and education, namely arising in ancient Greece but also existing under other names in many cultures, from Indigenous Americans to ancient China. Basically, we think of rhetoric as the practice and study of the ways people use symbols, especially language, to get other people to think or act. I often tell students that rhetoric is someone saying something to someone else in some way at some time in some setting for some purpose. In the time of AlphaPersuade, those someones and somethings and ways and purposes and times and settings and purposes are increasingly mediated by AI, and they are increasingly AI in themselves. Roger Thompson, the organizer of the summit, said that he wanted concerted attention to ethical rhetorical thinking to be embedded in industry, lest AI persuasion be used for “less than virtuous activities.”

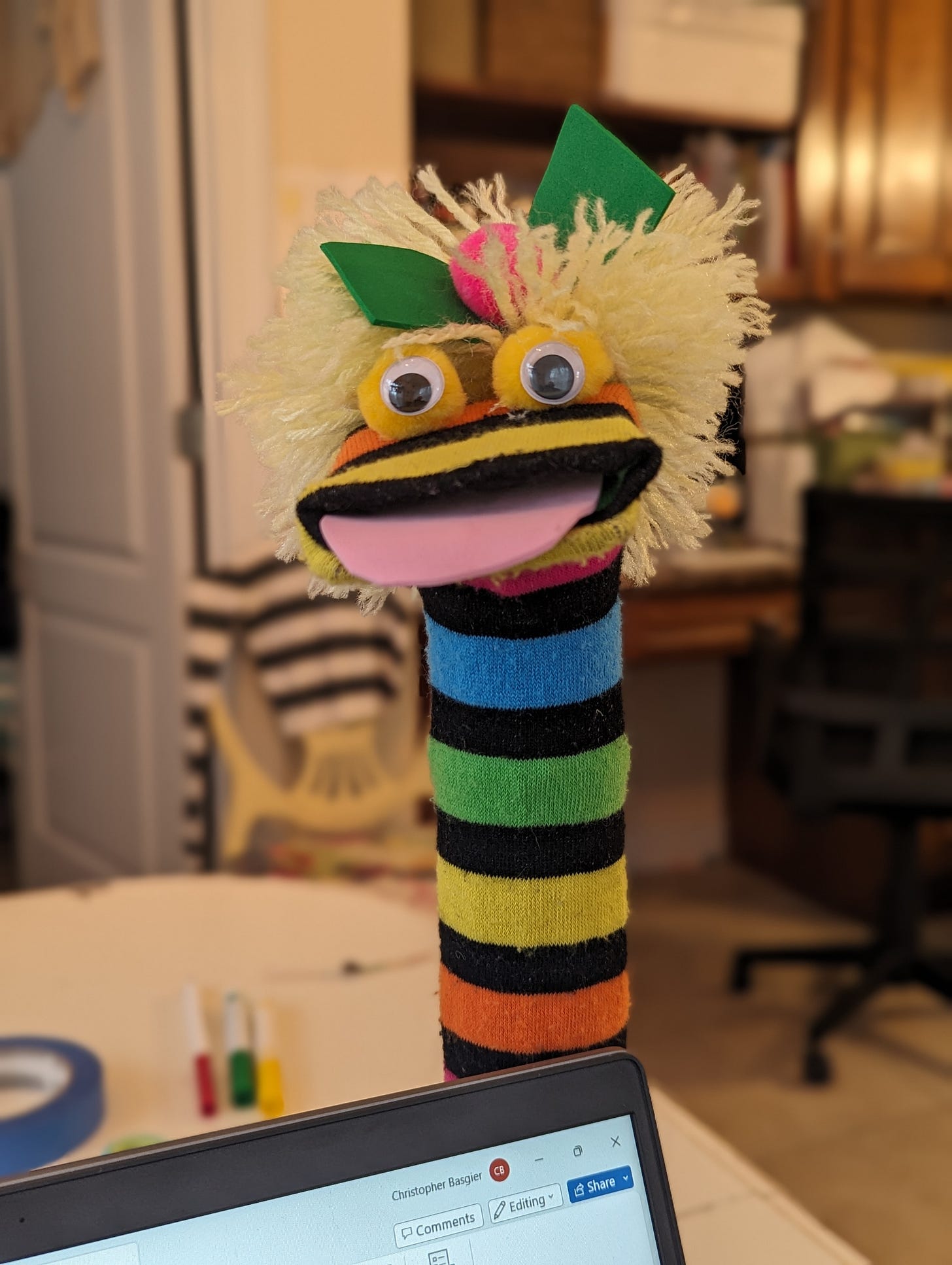

Connie the sock puppet accompanied me in writing this post. She reminded me that ethical persuasion requires that we not treat our audiences as mere puppets, but as whole thinking, feeling, acting people.

From where I sat, the keynote addresses probably went in reverse order.

Olaf Kramer introduced Aristotelian rhetoric as one potential framework for building an ethical AI rhetoric, one that could drive the production of AI models, the use of AI platforms, and the critique of AI-generated texts.

Tiera Tanskley shared the myriad ways in which anti-Black bias is baked into AI applications, especially ones that are already being deployed in schools for surveillance purposes, and she shared creative, student-led AI projects designed to improve the lives of underrepresented students and communities.

Casey Mock critiqued AI’s potential to engage in deception even without explicit human prompting.

The summit ended with a roundtable and a series of questions about bias, harm reduction, and writing pedagogy in response to generative AI—a solid end to the event. But I say the three keynotes should have been reversed so that we might start with the Tanksley and Mock, who really provided us with the core problems posed by AlphaPersuade as a phenomenon, and then Kramer, who began to provide a rhetorical answer.

I should point out, however, that Tanksley’s presentation was in some ways the most practical because she actually demonstrated how the communities most affected by generative AI might be empowered to seek out or create their own alternatives that break open what she called “fugitive cracks in the code.” Just one example: one of her student groups devised a robot called Jordan that is trained to talk to young people about Black history and culture and provides microaffirmations—all in response to efforts to ban classroom discussions of critical race theory and Black history.

Still, the point of the summit as I understood it was to propose a framework for ethical AI persuasion, one that developers of all sorts could adopt and adapt to their local use cases. The effort responds to what I see as a fundamental problem. Put simply, right now, AI is not trustworthy. And yet, many of us are using it as if it were.

We’re used to thinking about AI’s basic lack of trustworthiness in terms of hallucination and bias, but it is more fundamental than that. According to Kramer, AI has accelerated the breakdown of common cultural ground precipitated by social media manipulation over the last decade. In short, we are all caught in algorithmic bubbles that put us in very different conceptual and ideological worlds from our neighbors.

Ironically, according to Kramer, generative AI is essentially a machine for identifying rhetorical commonplaces because it uses algorithms to identify common forms of expression. However, generative AI is poised to exacerbate information overload, to the point where no one has really read the same texts, watched the same shows, or listened to the same music. There is simply too much to take in, and few reliable mechanisms for establishing and communicating quality. Furthermore, Kramer elaborated, that when we talk with one another, and write to one another, we must build common ground. We use commonplaces to ensure that we aren’t misunderstood and to communicate our understanding of others. But generative AI doesn’t do this, not really. Oh, it may occasionally repeat a query, but that’s only feigned understanding, not a true negotiating of meaning that results in shared ways of interpreting the world. After all, AI is fundamentally not engaged in the (rhetorical) act of interpretation. All this means that we humans have vanishingly small common ground on which to establish trust with one another.

So what role can rhetoric play in a world in which AI is fundamentally not trustworthy, and in which we cannot trust the texts we read? Kramer offered two ideas. Invitational rhetoric, first proposed by Sonja K. Foss and Cindy J. Griffin, self-consciously seeks to facilitate understanding with audiences rather than dominate those audiences; it invites those audiences into equal dialogue to promote their own self-determination. Meanwhile, bridging rhetoric, proposed by John S. Dryzek, explicitly acknowledges that our audiences will often have vastly different needs, perspectives, ideas, and commitments from us. Both ideas require us to honor others and to communicate with them with dignity and respect, rather than see them as mere pawns in our rhetorical, ideological, or economic games. To get inside someone else’s discourse and walk around for a bit can be difficult work, but we can come out the better for it because we can end up with broader perspectives and the creative, complex interplay of similarity and difference—rather than the bubbles of rhetorical and ideological sameness that increasingly characterize our public and political lives. And Tanksley reminded us that to put these kinds of rhetorics to work, we need representation of many other voices, bodies, identities, and perspectives. If we can teach, learn, and develop AI products in circumstances that require invitational rhetoric and bridging, then the AI tools that result might be more likely to include these rhetorics in their base algorithms.

As much as I like this vision—and wish it had been explored in more detail—I wonder what incentive there is for companies to engage in this work. Unfortunately, Mock and his colleagues at the Center for Humane Technology have demonstrated that the profit motive, and perhaps even the “because we can” motive of technological progress, too often far outweigh the altruistic and democratic motives that might underlie ethical AI persuasion. Then again, imagine for a moment that you work for a company in which AI is a business tool, not a product. Wouldn’t you want your AI applications to be trustworthy? Could the company who can validate and sell trustworthy AI have a leg up over those who cannot? This won’t stop bad actors, but perhaps someone out in industry can find a way to create a market for ethical AI persuasion. Otherwise, I have a hard time seeing how we will get there and scale it up.

Thanks, it is great to read this overview of the event and your reflections on it!

It might be worthwhile to explore current norms around “trustworthiness.” Language bots are destined to err because the machine’s product is “written” based on token probability. Many of its “errors” are absorbed easily in the uptake because they’re not so far off they startle anyone. Is “trustworthy” used in the sense of “Toyotas are trustworthy”? Or “She is trustworthy with sterling integrity”? There is buried complexity here. Is it meaningful to think of AI as “trustworthy” or “not trustworthy” in human terms? Is there a need for a theoretical framework? Are any available?